On a platform at the front of the hall was a school teacher’s desk, a single chair, a strip of carpet and a single-pole coat stand. Like eager rock fans, we were student writers waiting in the summer heat to hear the great writer read.

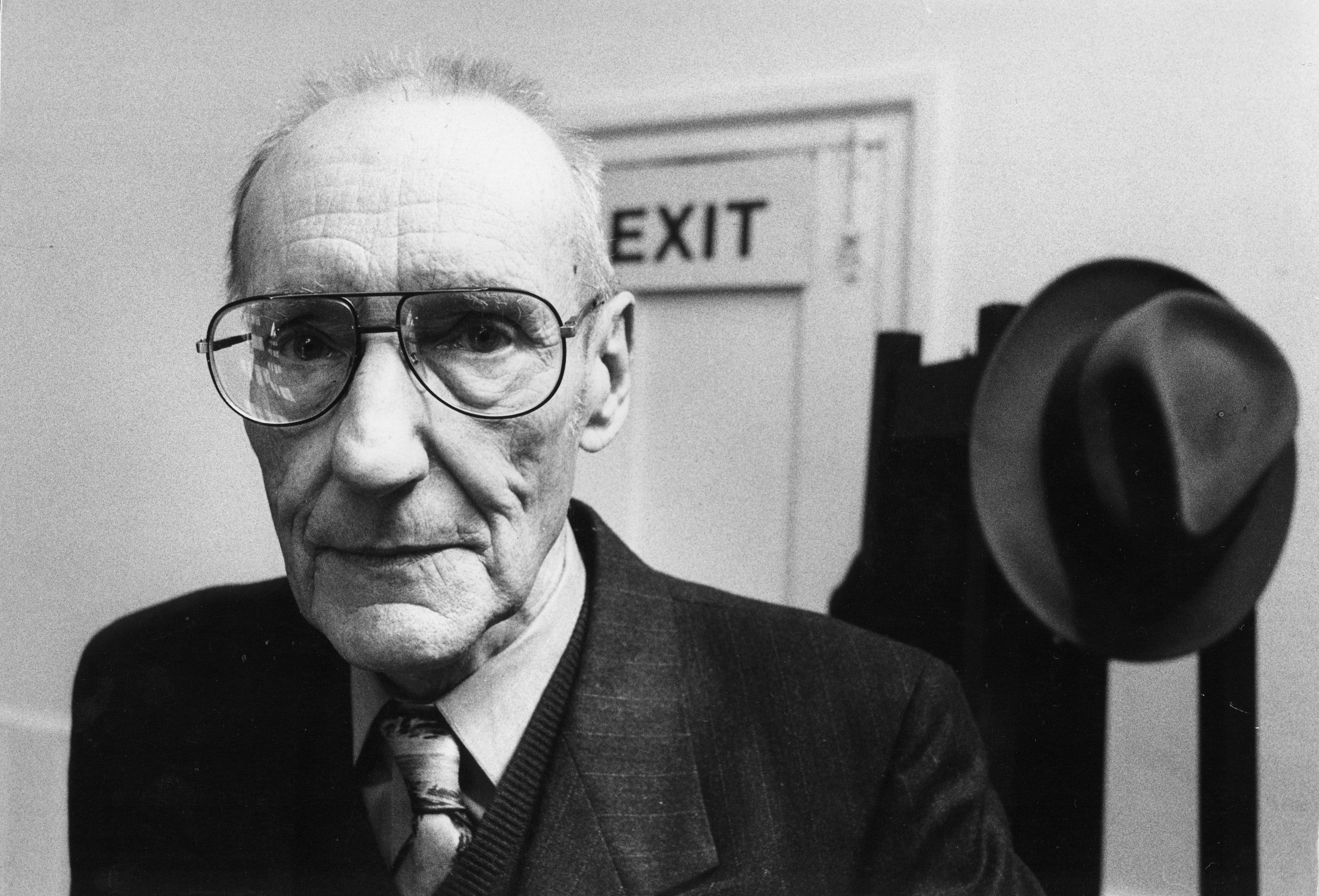

Finally, he slouched into the hall like a beast to Bethlehem, climbed to the platform alone, and meticulously hung his fedora and raincoat on the stand. The audience held its breath as he settled himself at the school desk, parsed the grammar of his business suit, vest and tie, and opened a binder of text. Head down, he started to read.

It was prose. We were ready to love it. But, it was bad prose. Truly bad prose.

He finished the section, slowly took off his glasses, and looked up.

“What shit,” he said. He paused. “William Faulkner.”

He turned the page and read more. He punctuated the new section with “crap.” And then identified the author: “Hemingway. Utter crap.”

Like death calling the roll, he read from the work of famous authors captioning each with epitaphs of “shit,” “crap” or “utter crap.”

Finally, he closed the binder and growled at us, “and you think you can write.”

Without another word, William Burroughs rose, slipped on his beige raincoat, adjusted his fedora and walked out into the summer heat.

I don’t know why, but somehow it was invigorating to have the author of Naked Lunch condemn our naive attempts to write. Burroughs wanted to puncture the hubris of young writers. But, he was also saying that writing utter crap is part of the process—whether you’re Faulkner, Hemingway, Emily Dickinson, Little Lulu or William Burroughs.

Burroughs pulled back the curtain to show us literary lights fumbling in the dark—making mistakes, producing dreck.

We may be enamored of Ernest Hemingway’s “effortless” prose and assume that he had natural mastery that we could never obtain. However, examine his working drafts archived at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston. At the top of one page, he has labelled it “Draft 42.”

Even after 41 rewrites, the page is littered with emendations, cross outs, and arrows to shift paragraphs.

Keep in mind that Hemingway had to type each draft by hand. So, the ease and simplicity of his prose emerged slowly through multiple drafts and long hours. And, Burroughs still finds passages that slipped through Hemingway’s edits and live on as “utter crap.”

Can you accept that “utter crap” is part of your life and work?

English poet W.H. Auden said that “the best poets write the most bad poems.”

Bad or good, the best poets write the most poems. The best composers, artists and writers are prolific, engaged in constant practice to master their domain. Practice naturally includes failures. Failures sharpen the eye, teaching you to ask better questions.

We have a false belief that rising from neophyte to expert is a steady ladder with no return. We even toss around the phrase “taking it to the next level” as if all skills and talents were a part of an ever-rising stairway.

But, the process of innovation is more like a game of chutes and ladders. You may climb to a moment of success, but the next roll of the dice will just as likely send you back down a chute.

As Burroughs pointed out, we all slip down the chute from time to time. The only cure is to persevere. Writing more bad poems may or may not elevate you to “the next level.” But, it is certain that you will never improve by not writing at all.

Often we face a vision gap with our ideas. The initial idea has a pristine, crystal quality. You imagine and thrill to its beauty, its potential, its freshness. But, something goes awry as you take your idea from your inner exaltation to fashion it outside your mind. The colors don’t blend, the words don’t flow. The excitement dims to despair. We compare the awkward 3-legged dog we produce to the brilliant flying horse we originally imagined.

Persevere. Train the three-legged dog to fly.

Everyone faces the vision gap. Everyone trudges through bad work. Burroughs wrote his own “utter crap.” Go write yours and move on.