In his first exhibition (1940), Bill Traylor’s art work was described as “primitive.” In New York (1943), it was classified as “folk art by an old Negro man.” It went into storage, unseen for 33 years. Then, it was labeled “Black Folk Art” by the Corcoran Gallery exhibition in 1982. Along the way, his work would be called “naïve,” “self-taught,” and lumped in with “psychotic art.” Now, it is known as “outsider art.”

In 1942, $2 for a drawing was offered and refused; in the early ‘80s, $150 made his work “a hard sell;” then in 2002 one painting sold for $250,000.

What changed?

Bill Traylor and his art are still the same. What changed is society’s perception of what is creative and who can be creative. When he died in 1949, Bill Traylor’s drawing was not art; not creative in the eyes of the world. Today, Bill Traylor is considered creative, some of his drawings worth thousands each.

***

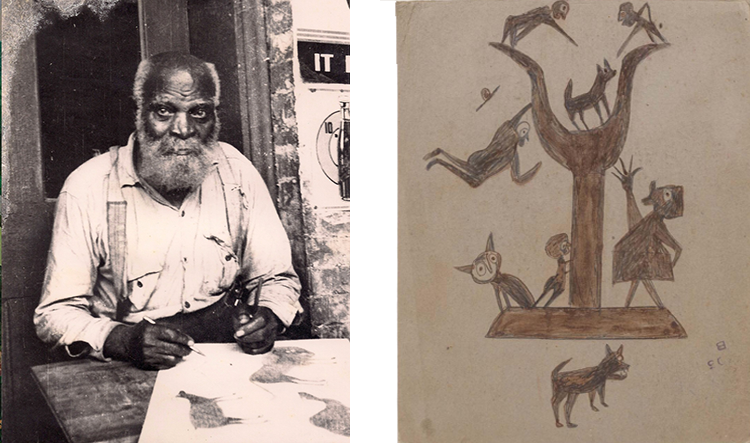

During the Great Depression, Bill Traylor was homeless, spending his days sitting on the sidewalk of Monroe Street in downtown Montgomery, Alabama, close to the state capitol. At night, he slept in the back room of the Ross-Clayton Funeral Home. One day in 1938, Bill Traylor picked up a pencil, salvaged a piece of cardboard, and began to draw. He was 85.

From then on, Traylor filled his days by drawing whatever he saw or remembered of his life. He was born a slave on the Traylor plantation 40 miles north of Montgomery in 1853. After the Civil War, his life of slavery barely changed: he became a sharecropper for the white Traylor family.

When “my white folks had died and my children had scattered,” he moved in 1928 to Montgomery to work in a shoe factory until rheumatism forced him out of his job and onto the streets.

About a year after Traylor started drawing, a young, white artist, Charles Shannon, became intrigued by Traylor’s work. They became friends. Shannon brought poster paints, brushes, and drawing paper to Traylor. Shannon later wrote that Traylor:

…worked steadily in the days that followed and it rapidly became evident that something remarkable was happening: his subjects became more complex, his shapes stronger, and the inner rhythm of his work began to assert itself.

In 1940, Shannon organized an exhibition of 100 of Traylor’s drawings in the New South art and literary center, founded by Shannon and his friends in Montgomery. It was the only exhibition of his work Traylor would ever see. Not a single work sold.

Shannon reached out to the art world in New York City securing an exhibition at a school in Riverdale. “Bill Traylor: American Primitive (Work of an old Negro)” organized by the director of education for the Museum of Modern Art, was up for two weeks in 1942. Alfred Barr, the founding director of MoMA offered to buy several Traylor drawings: one dollar for each small one and two dollars for the bigger drawings. Shannon was insulted and refused to sell.

The world was at war and Shannon and his friends enlisted. The New South art and literary center was abandoned.

Bill Traylor kept drawing, finishing anywhere from 1200 to 1600 works of art before he died at 96 in 1949. After the war, Shannon put Traylor’s complete body of work into storage.

Thirty-three years after Traylor’s death, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. included 36 pieces by Traylor in the exhibition, Black Folk Art in America 1930-1980.

At the time of the Corcoran exhibition, 1982, a Philadelphia art gallery offered Bill Traylor drawings for $150 each. The works were “hard to sell.”

Charles Shannon died in 1996. Weeks later, The Metropolitan Museum of Art displayed one of Traylor’s drawings, not as an example of African-American folk art, but in an exhibition titled A Century of American Drawing from the Collection.

On September 28, 2018, running for 6 months, the Smithsonian Museum of American Art will open the largest Traylor exhibition ever. In December 2017, Traylor drawings were auctioned by Sotheby’s alongside work by John Singer Sargent, Frederic Remington and Georgia O’Keefe. Traylor’s twenty-one drawings sold for $770,000.

The outsider is now on the inside.

Bill Traylor’s exodus from anonymity to Sotheby’s glory demonstrates how creativity is determined by domain gatekeepers. Traylor did his work for his internal satisfaction. The sources of inspiration were his own: what he remembered or observed.

Traylor’s work is clearly original. But, in his lifetime, less than a handful perceived its value. Even the term “outsider” implies a line which one must cross to be recognized as creative: those on the inside must invite the outsider in.

As more outsider artists have been discovered, commonalities have emerged:

- The outsider worked in isolation from society and far from existing schools of art.

- The outsider has been “found” by an insider and invited to show, sell or exhibit work.

- The outsider must have a story which authenticates his suffering, such as insanity, poverty, racism or disability.

- The outsider is self-taught, does not seek recognition for the art, and may not even consider herself an artist.

- The outsider is recognized after she dies.

Outsider art may also be perplexing. It was originally disdained as one of the trustees of MoMA wrote in 1943:

The unfortunate part of the exhibition is that it includes a number of things that are ridiculous and could hardly be included in any definition of art.

Alfred Barr, the first director of MoMA, who had offered pennies for Traylor’s work, held a retrospective of the paintings of Morris Hirschfield, a manufacturer of slippers, who began painting upon retirement. Hirshfield had no formal training; his paintings were dubbed “primitives.” The MoMA trustees were shocked and took the first steps toward firing Barr for his lack of taste and other shortcomings. Hirshfield’s crime against culture? His nudes had two left feet. Apparently, he couldn’t or wouldn’t paint right feet.

Left feet left behind, Hirshfield paintings now fetch 6 figure prices in the art market.

Outsider art is as old as hominids painting in prehistoric caves. There are artists everywhere, in every corner of the world. Who decides what demonstrates creativity and, therefore, what is art? It is not the individual who makes the art, who remains an outsider until called into the art world.

The line between outsider and insider, between creative and non-creative is drawn and enforced by the insiders. From the time of Bill Traylor’s death until now, the only thing that has changed about his work is how the insiders view creativity.