Are you ever tangled up in a tough problem, sleep on it, and then wake up with a solution? Do ideas come to you in the shower, on a walk, or doing the dishes? These ideas come to you through incubation—a time of mental rest (or distraction) with no conscious thought. When we are stumped—puzzled and frustrated—a night’s sleep or a time of idle thought will help.

In 1881, the French polymath, Henri Poincaré, was ensnarled in a difficult math proof. He wrote:

“For fifteen days I tried to demonstrate that any function could exist, similar to what I have called Fuchsian Functions, [now known as automorphic functions] but I was very ignorant, and every day I sat at my desk. I spent an hour or two, I tried many combinations, and I came to no results.”

Poincaré was a professor at the University of Caen but was still connected with the School of Mines where he had studied. With the math challenge unsolved, he traveled for geological study in Coutances, 107 kilometers away:

“The events of the trip made me forget my mathematical work; having arrived at Coutances, we entered an omnibus to go for some sort of promenade; at the moment when I put my foot on the step the idea came to me, without anything in my former thoughts seeming to have prepared for it…”

After his epiphany on the steps of the omnibus, Poincaré returned to Caen to verify his idea.

Poincaré turned to incubation to crack his most intractable problems. In 1904, Poincaré discussed his methods in his book The Foundations of Science. In a chapter called “Mathematical Creation” he described being stuck in a mathematical quandary:

“Disgusted with my failure, I went to spend a few days at the seaside and thought of something else. One morning, walking on the bluff, the idea came to me, with just the same characteristics of brevity, suddenness, and immediate certainty…”

Even his daily work schedule seemed to depend on alternating periods of focused mathematical work followed by non-mathematical work or idle thought. He limited his mathematical research to four hours a day, from 10 am to 12 noon and from 5 pm to 7 pm. Poincaré:

“Often when one works at a hard question, nothing good is accomplished at the first attack. Then one takes a rest, longer or shorter, and sits down anew to the work. During the first half-hour, as before, nothing is found, and then all of a sudden the decisive idea presents itself to the mind. It might be said that the conscious work has been more fruitful because it has been interrupted and the rest has given back to the mind its force and freshness.”

However, the brain does not rest. It appears that during dormant time or sleep the brain is busy rearranging thoughts, ideas, and information into different associations. Research conducted at the University of San Diego “support the hypothesis that the brain is subconsciously spreading activation of the previously activated nodes.” In other words, the brain networks you first use to address the problem reach out to other networks to find new and enlightening associations.

The study found that an incubation period of any kind improves problem solving. However, a successful incubation requires previous knowledge and thought. They also found that sleep—particularly REM sleep— “enhanced creative problem solving for items that were primed before sleep.” The benefits of sleep incubation accrued only with prior thought.

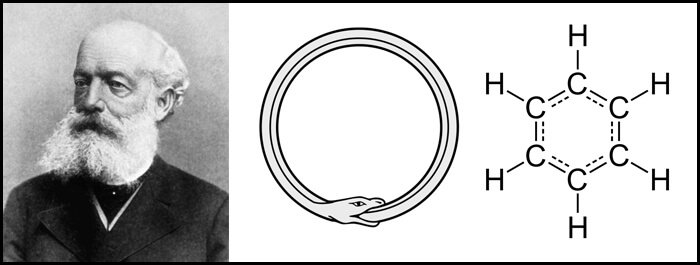

Friedrich August Kekulé, the preeminent chemist of the 19th century, claimed that his major achievement, recognizing the chemical structure of benzene, came to him in a dream as he dozed by his fireplace.

At a dinner in his honor, Kekulé told the story in his speech:

“As if by a flash of lightning I awoke; and this time also I spent the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis. Let us learn to dream, gentlemen, and then perhaps we shall learn the truth…. but let us beware of publishing our dreams before they have been put to the proof by the waking understanding.”

Like Poincaré, Kekulé followed his insight by arduous study. The inspiration emerging from incubation must be primed by prior work and then verified by subsequent work.

Let us learn to dream as we work. Let us have the wisdom to push forward and to step back in our creative struggles.