“Sometimes, I had to spend a whole day mixing a boiling mass with a heavy iron rod nearly as large as myself. I would be broken with fatigue at the day’s end. …I was then annoyed by the floating dust of iron and coal …”

1899

“Don’t you find it delicious to have a little tiny being to love? As for me, I adore little babies, but that doesn’t prevent me from also loving my big seven-year-old daughter.”

1904

At first glance, we are likely to attribute the first statement to a man and the second to a woman.

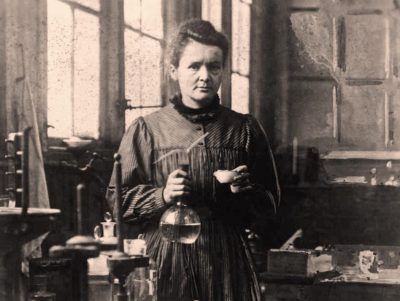

Marie Curie made both of these statements.

However, based on cultural expectations, the realm of children and babies is separated from the toil of boiling pitchblende over an open-air cauldron. In the 19th and early 20th century, mental and physical labor fell to man because “Woman is not a brain, she is a sex… She is not good for anything but love and motherhood.” Yes, love and motherhood and good enough to discover radium and polonium and become the only person to win the Nobel Prize in two different science disciplines.

Marie Curie should have been awarded another Nobel Prize for successfully juggling family life and a scientific career. She was as passionate about science as she was about her family.

“Children and the laboratory require the constant presence of those concerned with them,” her husband, Pierre Curie, wrote, “sometimes, she [Marie] finds her double task beyond her powers.”

Pierre Curie was more enlightened than his scientific colleagues. Marie was awarded the Prix Gegner, a scientific prize, but the judges could not notify her except by writing a letter to Pierre asking him to tell her.

She was born Marie Sklodowska in Warsaw in 1867, the youngest daughter of two educators. Her father believed that every moment of life was an opportunity to learn, and therefore, to be enjoyed. He and his five children cut out magazine pictures to make collages; he guided his children on “noisy” world tours of “continents and countries, cities, mountains and rivers” all represented by painted wooden blocks they scattered across the floor. Throughout her life, Marie would tackle her toughest problems by sitting on the floor with her work spread around her.

Marie learned quickly and often unnoticed. Her older sister once stumbled through her reading lesson. Younger by two years, Marie read the sentence aloud easily. No one in the family knew she could even read. Marie wound up in tears: “I didn’t know I wasn’t supposed to do that. . . but it was so easy!”

As Marie progressed to school, she came face-to-face with a maze of inexplicable rules imposed by the Russian occupying government. The children were not allowed to speak Polish even to each other. They were conscious of spies watching them. Classes were conducted in Russian by Polish teachers who were subject to surveillance and official visits. Marie, the smallest and most adept in her class, was usually chosen to recite in Russian for the visiting inspectors. In her autobiographical notes, she chose the word “timidity” to describe her fears of recitation for the Russians, but in an earlier draft she admitted that she “wanted always to raise my little arms to shut the people away from me, and sometimes, I must confess, I wanted to raise them as a cat its paws, to scratch! . . .”

Resistance to the Russians was a way of life. It was the duty of every patriotic Pole to fight for Polish freedom. Marie and her best friend walked to school passing a monument built by the Russians. Twice a day, each of the girls defiantly spit on the obelisk.

Marie was also surrounded by strong, independent women. Her mother was the head mistress of a girls’ school. Her aunts pursued higher education. One aunt managed her husband’s estate because he was indolent and incompetent. Yet, as she graduated from lyceum, Marie’s choices were limited: teach or marry. She took a position as a governess on a country estate, continuing to study in rare quiet moments late at night. In defiance of the Russians, she organized clandestine reading classes for the children of neighboring peasants. Similar teachers had been arrested and shipped to Siberia.

Although diligent, her studies were not focused. She did not know whether she wanted to study literature or sociology or science. She complains that her dreams are “so commonplace and simple that they are not worth talking about.”

She began a 4-year relationship with the oldest son, a math student. They planned to marry, but his parents objected to her low status as penniless governess. The son eventually sided with his parents. Marie wrote:

“Some people pretend that in spite of everything I am obliged to pass through the kind of fever called love. This absolutely does not enter into my plans. If I ever had any others, they have gone up in smoke; I have buried them; locked them up; sealed and forgotten them…

She then adopts what could well have been the guide for the rest of her life:

“First principle: never to let one’s self be beaten down by persons or by events.”

Back in Warsaw, she and her mother and sisters helped organize a secret school for women known as the Flying University. Classes were held in homes, unused buildings and churches.

Somehow, Marie gained access to a laboratory where, alone, she attempted experiments out of a textbook with mixed results. But, she reported an intense satisfaction when an experiment succeeded as expected.

From Warsaw, she traveled to Paris where she studied physics and chemistry at the Sorbonne, living in a student garret so cold that she slept under all of her clothes. She studied constantly feeling the great pleasure of the “liberty” to learn anything and everything.

She was not the only woman studying science at the Sorbonne; nor was she the only woman eager to learn at the Flying University. Most of the women around her were ambitious, eager to put Polish women in leadership roles. So, why was she able to achieve such astounding success?

Identifying causes and turning points in one life is impossible to do with certainty. We can only speculate. Marie Curie had more than the requisite intelligence. She grew up with a love of learning. And she felt the need to honor the higher calling of Polish patriotism.

Reading through her biography of her husband and her own brief autobiographical notes, there are two reoccurring themes: fatigue and consecration.

After the discovery of radium, both Marie and Pierre frequently comment on their fatigue. They seek the solace of seaside and mountain walks to combat what seemed to be endemic fatigue. They did not travel to Sweden for the first Nobel Prize because of fatigue. They also seemed unwilling to examine how working with radium affected them. Pierre’s fingers were so badly burned that he had trouble dressing himself. Even when lab animals died and there were reports of human deaths, they did not change how they worked. In addition to fatigue, they were plagued with mystery ailments, inexplicable aches and pains. But, they had no intention to stop or even slow down. They were driven by an intense desire to understand radium, even while they were being physically consumed by radium.

Marie called it consecration. She wrote of her father-in-law that his ultimate wish had been to “consecrate his life to scientific work.” During their courtship, Pierre asked her often to share in “his dream of an existence consecrated entirely to scientific research.”

Consecrated usually means exclusively devoted to a divine purpose—though it can be secular as well. Marie and her husband were secular, reliant on only empirical evidence. But they felt the divine in science. She ran her laboratory as if it were a “religious convent.” She shared Louis Pasteur’s view that the laboratory was a “sacred place” of peace and hope for humanity.

Marie Curie was consecrated to family and to a life of science. Was it this sense of consecration that gave her the courage, stamina, and intelligence to change the world?