“What are you thinking about?”

“Nothing.”

This is a common exchange between two people—say two friends, lovers, or husband and wife. To respond by saying “Nothing” usually indicates that we don’t want to share what we may be thinking. Or, that the interruption has banished a moment of reverie and we have forgotten.

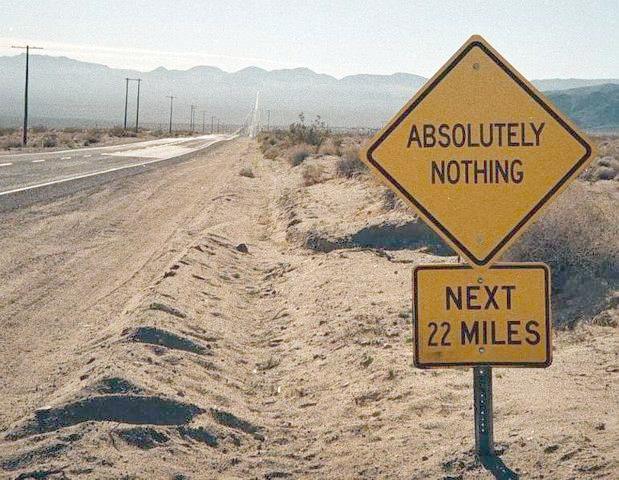

But, is it ever possible that someone is thinking nothing?

One can be deeply engaged in thinking about the complex concepts of nothing such as zero, a perfect vacuum or outer space. The idea of the numerical zero dates to India in the 5th century, C.E.—fairly recent considering that “in the beginning there was nothing” according to Genesis.

But, thinking of nothing? Can one drain the mental swamp to find dry land?

It is a popular myth that you can make your mind go blank through meditation, that meditators empty their brains of all thought and distraction to achieve a state of nothingness. However, the mind is still in flux. Thoughts will intrude on meditation. The meditator learns to dismiss or “let go” of mental intrusions by returning to a specific mental focus in that moment—such as closely tracking your breath.

Experienced practitioners describe a sense of harmony within their lives achieved through meditation. They speak of improved mood and cognitive skills. Brain scans do show structural differences between meditators and non-meditators, particularly in brain areas devoted to the regulation of emotion. On the other hand, brain scan studies have also established structural brain differences in musicians, cab drivers, and jugglers.

Meditation seems mysterious. It can be accompanied by religious trappings like incense, chimes and monks in robes. (Meditation is a part of the spiritual and mystic traditions of nearly all religions.) At its core, it is a solitary act of deliberate silence. But, it is not an internal, mental silence. It is focused, not reduced mental activity.

Scientists believe that there are two primary networks in the brain: an extrinsic and an intrinsic network, also known as the default mode network. (Neuroscientists should never be allowed to name things.)

The extrinsic network plays an executive function of planning; the default mode network appears to be a source of imagination and visualization. In theory, these two networks function like a seesaw—when one is active, the other is less active.

However, researchers found that both networks were active in Buddhist monks meditating in an fMRI scanner. Their sense of unity comes through heightened brain activity, not lessened. Does meditation draw more of the brain networks than other thinking? Is this heightened brain activity only the function of meditation; or, can the intense focus of other activities—such as music, painting, math or woodworking—also provide the heightened activity of the two networks?

The brain does not rest. fMRI brain scans show brain activity no matter how neutral and inactive the patient tries to be. We cannot pull the brain into a garage and shut if off for the night. It is always working.

For example, many have had the experience of going to bed stumped, unable to solve a problem. Then, when we awake, a solution miraculously appears in our minds. I often wondered: if the solution appears first thing in the morning, shouldn’t I charge the client for 8 hours of sleep?

Brain neurons fire randomly and constantly. Approximately, a million synapses are altered every second. We don’t know why. Housecleaning? Sorting the filing cabinet of the mind? We don’t know what purpose or meaning the random firing serves.

There is brain activity that we cannot monitor on our own. The conscious mind is only a spectator awaiting the verdict of a sequestered jury hiding out in the recesses of our minds. Sometimes we are the last to know what our brains are thinking.

The brain is never empty. And, nothing could be better than that.