Sometime before we left tricycles for bicycles, my brother and I played “men.” I was Mr. Black and he was Mr. Brown. We made phone calls and went to work. We turned our tricycles upside down, cranking the pedals by hand to make “popcorn.” Under the porch, the six supporting posts became phone booths. Mr. Black would make an urgent, long distance call from his phone booth to Mr. Brown standing in his phone booth 12 feet away.

In a quick consult, we agreed on the right action: make more “popcorn.”

We also played pretend baseball. I believed that a grand slam home run was when you hit the ball so far that the batter ran around the bases four times before the other team could find the ball and bring it back. The batter also announced the play-by-play and made rousing crowd noises.

Imagine cheering lustily for an arbitrary, made up game. Or playing a fictional character in a make-believe scenario. But, that’s children for you. We grow up, supposedly.

“When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

What are the childish things that the adult puts away? The diaper, the bib, the rattle and the crib?

Because we never fully put away the pretend play and role playing of childhood.

For example, each weekend stadiums and arenas fill with people engaged in the pretend play of sports, rooting for the home team as if the outcome of the game mattered beyond the sense of imagination. Sports media and advertising work hard to create meaning through this make-believe: “this is only the first time in history that a left-footed kicker has hit two doubles while playing point guard in the NHL.”

Adults even paint their bodies and dress as mascots. We wear the jerseys of favorite players so that one stadium can have over a thousand Tom Brady’s. We scream at the camera in passionate fury that “we’re number one,” insinuating that we embody the strength of the team. We pretend to be the team.

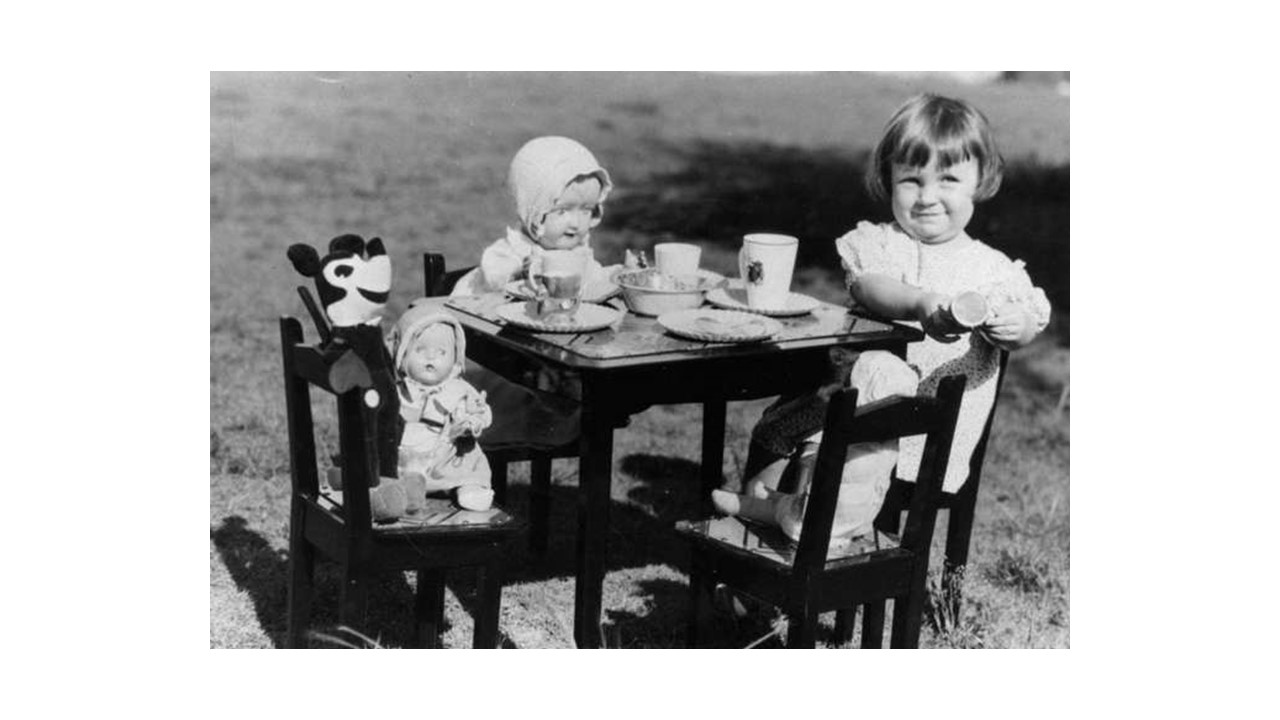

We begin to engage in pretend play as young as 24 months. A child hosts a tea party for his teddy bear and doll friends. He pours and drinks pretend tea. If the “tea” spills, the child will say “Uh-oh” just like adults. In this series of play actions, the child is setting up a chain of causality based on stipulations: the tea is stipulated to be real, so it can be sipped, shared, or even spilled like real tea. Though the floor is not wet, the spilled tea must be wiped up and the doll’s dress—if it got “wet”—must be changed.

This pretend play is not a distortion of reality. It is a reenactment with variations—an exploratory narrative based on the child’s knowledge of the world. (Facing incomplete knowledge, a child will improvise: a grand slam home run is four times around the bases, or, people go to work to make popcorn.)

Human beings use narrative to create meaning. We tell the story of our day or of our life. We abbreviate with tell-tale symbols to stand in for our full stories—“I’m an accountant,” “I’m from Iowa,” “I’m a Red Sox fan,” or even “same old, same old.” And, like children, we also indulge in fictional narrative as hypothetical chain of causality—action A leads to action B eventually culminating in Z. We read fiction, write plays, go to movies and watch sports to ponder what will happen if:

A ship captain becomes obsessed with a great white whale?

Your dead father appears as a ghost to tell you that the new king killed your father?

A lost love appears in your Casablanca café during the middle of world war?

A third string quarterback leads a 4th quarter rally?

The differences between an adult narrative and a child’s pretend play—both chains of causality—include length and complexity (sometimes.) If you’ve ever listened to a child’s story, however, its complexity can be overwhelming and unpredictable.

Children also place a greater premium on fun. Adults can become deeply entwined in fictional narrative—even to the point of life study and a PhD in English. However, pretend play stops when it ceases to be fun. Or, children change the stipulations so that the play can continue to be fun.

Pretend play by children is found in every culture. Is it practice for future adulthood? Is it the exploration of the child’s knowledge of the world? Is it pure escapism? Is it a valuable learning tool?

Apply all of these questions to the adult versions of pretend play and the answer is yes for both children and adults.

And, play is fun—a very human reaction to a challenging, dangerous world.